After World War II, US hegemony faced a unique challenge. African and Asian countries began liberating themselves from their colonial masters, whose armies could no longer sustain the oppressive violence needed to maintain their colonies. Capitalism had been thoroughly discredited—not only in the Eastern Bloc, where anti-fascist governments took power, but in Western Europe as well. Intellectuals, artists, and musicians in Western Europe increasingly embraced Marxism as the prevailing ideology. While US industrial power had an awe-inspiring reputation for producing unprecedented consumer goods, culturally, the US was viewed as a backwater that created no innovative works of art, music, or literature.

Classical music was seen as a European creation. Hollywood still had not perfected its blockbusters. The American authors who were known abroad such as Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck had socialist leanings, which would not be of any help for the US government officials who were trying to sell American capitalism abroad.

Historic.ly is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In the effort to win influence over the world, the US has two big problems: their actions around the world made it clear that the US wanted to replace former colonial powers, second, the racial discrimination in the US made it difficult to win influence in countries populated mainly by people of color.

Their efforts to win influence amongst people of color was severely hampered by the overt racial discrimination that black people faced in the USA. They could not convince African heads of state that they envisioned a partnership on equal footing, when most black people were oppressed at home through overt racial segregation and the more insidious economic discrimination.

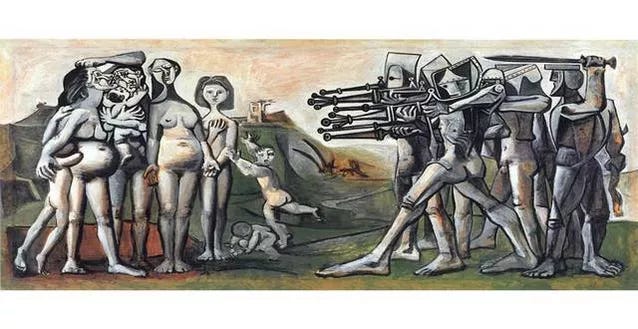

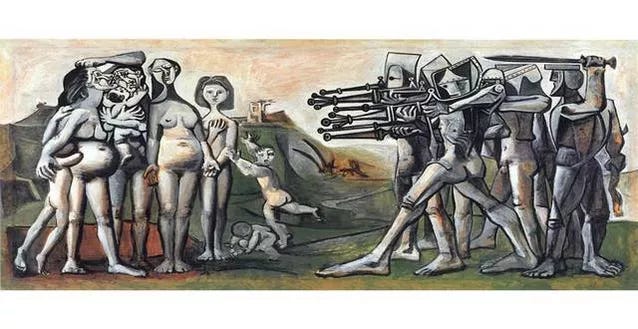

In Western Europe, the traditional leftist artists, in their expressions, used art for politics, which often highlighted the crimes of colonialism. For example, Pablo Picasso, who was a Marxist, used his art for political messages. One example is his painting “Massacre in Korea” which highlighted the atrocities committed by the US in the Korean war.

Massacre in Korea by Picasso

A conversation on the grounds of colonial crimes, was one that the US could now win. Therefore, the US strategy was to change the conversation. This problem was tackled by two agencies: the United States Information Agency, which was created in 1953, and operated under the state department and within US embassies. The CIA also took to sponsoring many umbrella organizations aimed at this effort.

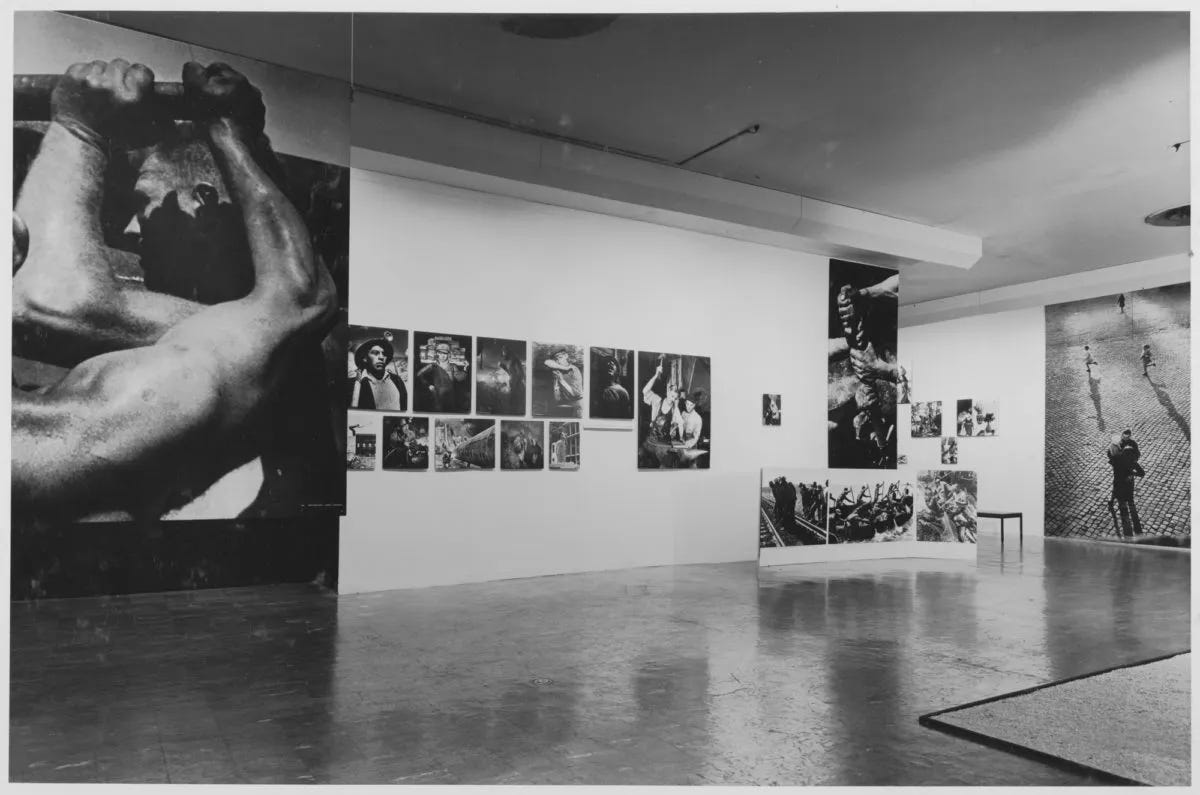

They focused on art forms that removed political messages from the traditional leftist art. One of the art forms that they chose to sponsor was modern art, whose abstract expressions steered the conversation about the boundaries and definitions of what is actually art and it steered the conversation away from political commentary. In fact, the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) was filled with national security ties.

MOMA was founded in 1929 by Abby Rockefeller. In 1939, her son Nelson Rockefeller became the President of MOMA. He was also appointed by the Roosevelt administration to serve as the Assistant Secretary of State in Latin America. Its executive secretary between 1948-1949, Thomas Braden went on later to join the CIA. In a Saturday Evening Post article entitled, “I’m glad the CIA Immoral”, he wrote that modern art “won more acclaim for the U.S. …than John Foster Dulles or Dwight D. Eisenhower could have bought with a hundred speeches.”

Under the secret patronage of the CIA, MOMA arranged many art exhibits all throughout the world. In fact, the State Department in 1946 spent thousands top purchase modern art pieces featuring artists like Georgia O’Keeffe and Jackson Pollack.

In the field of literature, the United States Government sponsored many magazines around the world such as London-based Encounter and the French-language Preuves. They featured writers who strived away from critiquing concrete actions of the United States to celebrating more abstract notions like “freedom” and “democracy.” This helped create what later CIA employee Cord Meyer described as a “compatible left.”

The field of music was used to combat the most heavy criticisms levied against the US, namely the brutal racial oppression faced by Black Americans. The US had an uphill battle of convincing many newly freed African nations that it was interested in being an equal partner, when Black Americans faced overt segregation and more insidious forms of economic discrimination within the USA. Their answer to this was to promote Jazz music. In one embarrassing incident, two Ghanian Diplomats faced discrimination inside a Denny’s in Delaware, which prompted the Eisenhower administration to desegregate a stretch of highway between New York and Washington, which diplomats frequently travelled between.

Unlike classical music, Jazz music could be touted as a uniquely American form of expression. It started in New Orleans, mainly from Black Americans, who would use a mix of rhythms and fast-paced improvisation. With predominant artists being mainly Black Americans, they could showcase them on a world stage, which would alleviate the charges of the US engaging in active racial discrimination.

Under these guises, the State Department arranged for “Jazz Diplomacy” tours around the world. They sponsored artists such as Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong to tour around Africa. Of course, being sponsored by the State Department did soften the harsh critics both of these artists had about the racism at home.

In 1954, after the US Supreme Court ruled in Brown vs Board of Education that segregation, was inherently unequal, the instructed the states to proceed to desegregate “with all deliberate speed.” But of course, most states did the opposite and tried to hinder any efforts at integration at every step. In 1957, when then Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus deployed the Arkansas National Guard to surround the Central High School, to prevent the nine students from enrolling in the school, Louis Armstrong’s critique was harsh and unwavering. He said, “The way they're treating my people in the south … the government can go to hell."

However, after accepting his position as a Jazz Ambassador in 1960, when asked about the race relations within the US, his reply was, “I don’t know anything about it; I’m just a trumpet player.”

On top of muting the critics of these once strong musicians, the Jazz tours did not only promote diplomacy, but they helped aid the efforts of the US National Security State, in other ways, unbeknownst to these musicians.

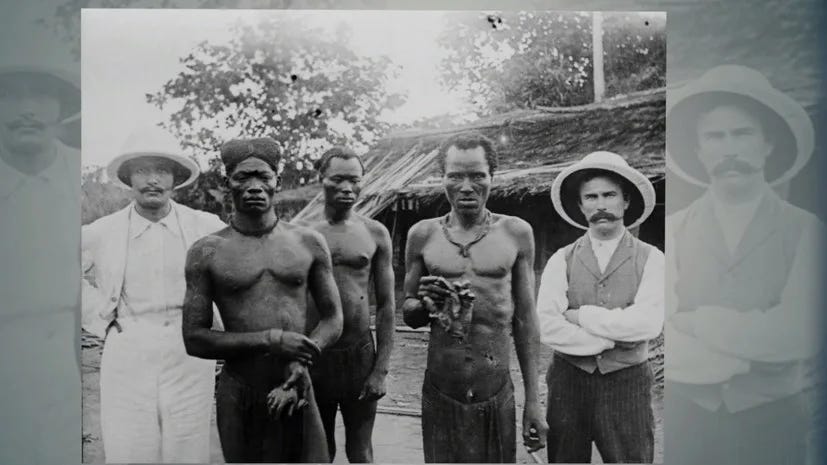

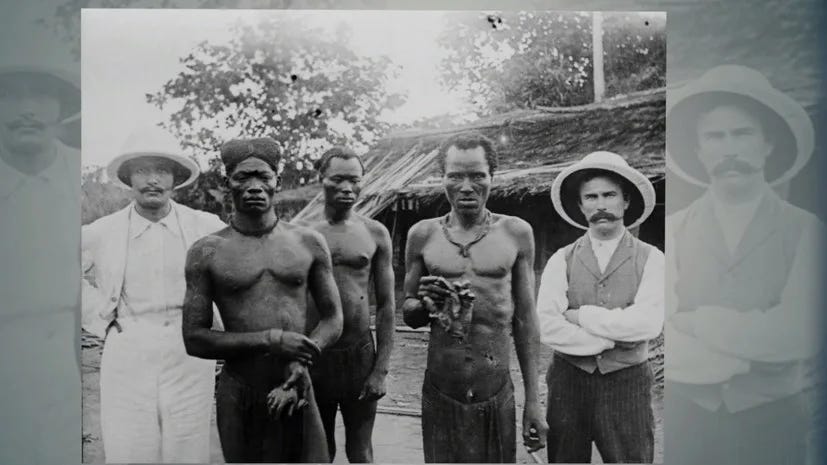

On June 30, 1960, Congo had just earned its independence from Belgium after one of the most brutal colonial rules. Joseph Conrad, in his book, “The Heart of Darkness” wrote about the depths of humanity’s depravity which took place in King Leopold’s Congo. King Leopold desperately wanted a colony, and nations such as the United States and the United Kingdom obliged in the Berlin conference by establishing the Congo Free State. Unlike other colonies, the Congo Free State did not belong to the country of Belgium, but instead of King Leopold’s personal fiefdom. With the patenting of rubber tires by John Dunlap in 1888, demand for a new resource skyrocketed exponentially. Congo, being rich in rubber trees was lucrative for the profit for the profiteers.

Brutality of the Free State of Congo Unprecedented

In order to meet the exorbitant demand for rubber, the Congolese people were forced to harvest wild rubber through daily quotas which was enforced through the vicious Force Publique, King Leopold’s personal mercenary force. Failure to meet the rubber quota meant that the Force Publique would chop off the hands of the Congolese villagers as one of the most brutal forms of retribution.

Later, in part due to the atrocities in Congo under King Leopold, in 1908, Belgium took over the management of Congo as Belgian Congo. Around this time, Congo’s rich deposits of copper became known, which led to the opening of the mining concession Union Minere, which exploited the rich copper deposits in the province of Katanga.

While Belgians exploited the minerals in the tune of billions of dollars, Congolese were left with very little to show for it. Besides the mineral-rich region of Katanga, there were not many highways joining the country together. Schools were few and far between and mostly serviced Belgian pupils. The Belgian colonization in Congo was so brutal that in 1960 when Belgian finally left Congo, the average life expectancy was 40.2 years. Diseases were rampant.

Amidst this backdrop, a young, visionary Patrice Lumumba was elected the first Prime Minister of an independent Congo, which became independent on June 30, 1960. During the independence day processions, Belgium King Baudouin took the stage, where he praised the King Leopold II. He also stated that he hoped the Congolese would prove worthy of the “trust” placed in them by the Belgian colonial powers. Soon afterwards, Patrice Lumumba took up the stage with a fiery speech that highlighted the brutalities of Belgian rule in Congo. He said, “We remember the ridicule, insults, and beatings we had to endure morning, noon and night, because we were ‘negroes’. We recollect the atrocious suffering of those persecuted for political opinions or religious beliefs. Exiled in their own homeland, their fate was really worse than death itself,” he said, recalling that this independence was indeed the fruit of a “struggle.”

Lumumba also expressed desire to use the vast mineral wealth in Congo in order to develop it economically. Immediately, this speech painted a target on his back where Washington and Brussels were concerned. On August 18, 1960, the CIA head Allen Dulles met with Eisenhower in order to plan the overthrow of Patrice Lumumba. Soon, the main plans were made, which involved supporting Joseph Mobutu and his militia to take over the country.

When Louis Armstrong began his tour in Congo in October, Lumumba was already under house-arrest. His tour was promoted in a west, as a way of distracting western audiences from the actual goings on in Congo. The first stop was Leopoldville (Kinshasa) where he played to a large crowd. The more curious aspect of his tour was the second stop: Elizabethville, which was what the capital of the mineral-rich province of Katanga was called.

While the US, formally, did publicly recognize Katanga as an independent republic, they provided the rebels with military support through back channels. The US had established a covert action program. Through, their allies in Apartheid South Africa, they created channels to recruit both mercenaries and also send arms to the rebel group.

While under the pretext of attending a Louis Armstrong concert, the CIA attache Larry Devlin, who was under the cover of being an embassy staffer was able to move freely in Katanga. Embassy staffers also met with the self-declared President in Katanga, without the US giving actual recognition. Ambassador Clare Timberlake went for the event, as well as the CIA chief Devlin. It was later admitted that ‘The object was to talk to Tshombe, the elected president of the Congolese province of Katanga, without recognizing him as the president of an independent state.’

While the concert itself did not enable the coup, it allowed for key meetings between coup-plotters and embassy staff to occur. It gave them the necessary cover to have these meetings without drawing attention to the planning of the coup. A few months after the concert, the Democratically elected leader Patrice Lumumba was assassinated. Of course, even without Louis Armstrong’s Jazz concerts in Congo, the CIA would probably have found a way to meet with key figures that enabled them to create an armed resistance to install the western-friendly Joseph Mubuto into power.

The mineral wealth of Congo remained in the hands of western companies like Union minere.

While the Jazz diplomacy ended in the 1990s, the State Department continues to sponsor similar programs in the interests of its national security state. Nowadays, much of the function of the CIA has been taken over by the National Endowment for Democracy, who continue to give grants to various artists and radio programs.

The US State Department and the US national Security state continues to use music and art to promote its agenda. Most recently, it named Rapper Chuck D, as the Global Ambassador for Rap, and we interviewed him about his transition from “Fighting the system” to “Representing the system.” In his interview with us, he tried to explain that “the devil does not use the same trick twice” and he is not being used in a similar manner as Luis Armstrong and other musicians from the past. But, only time will tell if that is indeed the case.